Artist Cai Guo-Qiang recently launched a fireworks project titled "Rising Dragon" in Gyantse, Tibet, sparking public scrutiny. This event, which touches on topics related to art, commerce, and environmental protection, has brought to the public's attention the profound ethical dilemmas that have plagued land art since its inception.

Several senior art critics told The Paper that this incident forces the art community to seriously consider the nature of art and the moral and ethical boundaries of art.

Large-scale contemporary environmental art projects often rely on substantial capital due to their high demands for technology, manpower, and venues. The in-depth collaboration between the "Rising Dragon" fireworks project and a renowned outdoor brand exemplifies this reality. When artistic expression is distorted into green marketing, art becomes a cultural tool of capital, often overlooking the equal relationship between humans and nature. Furthermore, these large-scale environmental projects are often approved in regions with weak ecological awareness and inadequate environmental regulatory systems.

Many online compared the fireworks display to a 2015 show hosted by the Swiss outdoor brand Mammut. Commemorating the 150th anniversary of the first ascent of the Matterhorn, Mammut organized climbers to ascend the Matterhorn's ridgeline before dawn, following the route taken by Edward Whymper's team in 1865. Headlamps illuminated the entire ridgeline, creating a chain of red light. In 2020, Zermatt, Switzerland, officially commissioned light artist Gerry Hofstetter to project encouraging messages about epidemic prevention onto the Matterhorn. Furthermore, Finnish artist Kari Kola transformed the Connemara Mountains of Ireland into the public art installation "Savage Beauty," using over a thousand emerald green and blue lights to highlight the majestic natural landscape.

However, the artistic expressions implemented on the Matterhorn and Connemara Mountains both use lights, and their impact on the environment is much smaller than that of fireworks.

Mammut light show on the Matterhorn

Connemara Mountain Light Show in Ireland

The Essence and Ethical Dilemma of Land Art

Land Art originated in the 1960s as a rebellion against the industrialized and commercialized art system. Some artists chose natural environments (such as seasides, wilderness, and deserts) far from the urban civilization of art galleries, museums, and other urban environments as venues for their artistic creation, engaging in many radical artistic practices. This movement was both an inevitable outcome of the innovative development of postmodern art and a passionate response to the cultural trends, ecological issues, and development concerns of the time. The core concept of Land Art lies in breaking down the boundaries between art and life, between the artificial and the natural, advocating a return to nature, using the earth itself as both the material and the venue for artistic creation.

The most famous examples are Christo and Jeanne-Claude's works "Running Fences" and "Wrapped Islands." Created in 1976, "Running Fences" saw the artist couple construct a temporary barrier stretching 40 kilometers across the California hills using white nylon fabric. The fabric flowed with the wind, interacting with the topography, light, and weather, transforming the landscape into a dynamic art installation. The project, ensuring ecological resilience through rigorous environmental protocols, embodied a philosophy of "ephemeral intervention" and was entirely funded by the artists themselves, rejecting commercial sponsorship. In 1983, the artist couple created "Wrapped Islands." They encircled 11 Florida islands with pink polypropylene fabric, creating a floating, colorful garland on the water surface when viewed from above. The project, which took three years to complete ecological assessments and government negotiations, ultimately lasted only two weeks. Despite controversy, it became a model for large-scale ecological art projects by mobilizing public awareness of the environment through art and promising to "leave no trace."

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Running Fence (1976)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Wrapped Island (1983)

The emergence of Land Art was a rebellion against the institutionalization of modern art. After World War II, Western art became increasingly commercialized and institutionalized, with art evaluation mechanisms, discourse, and ownership concentrated in the hands of a small number of art institutions, critics, and collectors. Artists like Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer chose to escape the urban art system and turn to remote natural spaces. They utilized various elements of nature in their creations, allowing their works to be stored and displayed directly in nature. This freed them from the confined spaces of museums and galleries, disrupting collectors' control over works and the hegemony of critics' discourse.

Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, 1970

In 1970, American artist Robert Smithson poured 6,000 tons of basalt and soil into Utah's Great Salt Lake, creating the 450-meter-long Spiral Jetty. Although Smithson stated that the work explored themes of entropy, decay, and the natural cycle—the levee appeared and disappeared with the changing water levels of the lake, ultimately returning to nature—critics viewed the work as altering the natural landscape of the lake. While seemingly a celebration of nature, it remained anthropocentric at its core.

The year before, Michael Heizer's Double Negative excavated two trenches approximately 450 meters long, 15 meters deep, and 9 meters wide in the Nevada desert, blasting and excavating 240,000 tons of rock and earth. While these works criticized traditional art's reliance on artificial space, they also fell into another misunderstanding: treating nature as a blank canvas, reshaping its forms according to human aesthetic will. Their drastic excavation methods also sparked widespread criticism, becoming a prime example of the ethical controversy surrounding Land Art's intervention in nature.

Double Negative, live performance in 1969.

From Land Art to Land Art Festival

Most of the above-mentioned cases occurred 40 years ago. Throughout the history of land art, there have been more or less cases of public concern or criticism caused by intervention in nature. As the public's awareness of environmental protection has strengthened, the number of influential individual works of land art has decreased, and it has gradually developed into a "Land Art Festival" that collects multiple art installations.

In 2000, Japan held the inaugural Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale. Unlike previous single-piece works in natural settings, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale featured a multi-art exhibition, aimed at bringing attention to and revitalizing rural communities. The event was initially intended to address the issue of population loss due to an aging population. By hosting art events and inviting artists to create in rural fields and unused homes, it encouraged a return of population and promoted rural regeneration. Later, Japan also held the Setouchi Triennale, where artist Yayoi Kusama's giant spotted pumpkin, placed on the seashore, became one of its most widely circulated works. These "land art" projects are seen as a crucial means of revitalizing local communities and promoting regional revitalization.

Echigo-Tsumari, Japan, is famous for hosting art festivals.

Regarding his view of Land Art, Wang Huangsheng, a contemporary art researcher, professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and former director of the CAFA Art Museum, told The Paper: "Land Art, from its inception, has moved from museums to spaces and the earth itself. It breaks through the conventions of museums, and in the process, creates a new relationship with the land. At the same time, Land Art should be problem-aware, addressing environmental, ecological, and social issues, rather than simply creating a beautiful spectacle. Secondly, from an artistic perspective, Land Art should create a unique visual expression of the environment or the issues it addresses, a form that has never been expressed before."

The development of Land Art in China incorporates unique Eastern philosophical and aesthetic concepts. The traditional Chinese concept of the unity of man and nature provides a profound ideological foundation for Land Art, giving Chinese Land Art practice a distinct character from that of the West—one that emphasizes harmony over confrontation, and integration over intervention. Over the past decade, with the growing influence of the "Land Art Festival," this type of activity has gradually emerged and garnered attention in many parts of China as a new force in local cultural systems.

A famous installation work in the "Art in Fuliang" Earth Art Festival in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi

Previously, the WeChat public account "Youth City" team reviewed the past decade of China's Land Art Festivals and divided them into five categories based on the different dominant forces: government-led, enterprise-led, industry-led, university-led, and local organization-led. There are also many well-known current cases, such as "Art in Fuliang," which was supported by the Fuliang County Government of Jingdezhen City in 2021. With the artistic director of the "Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale" and the "Setouchi Triennale" as a consultant, Kitagawa Toshiro, the project follows the "art creation" method and aims to revitalize the local area, intending to build Hanxi Village into a "roofless art museum."

Works exhibited at the Aranya Earth Art Festival

In 2023, the Aranya Earth Art Festival will be held at Aranya Jinshanling. In addition to art exhibitions, the festival will also feature a series of "Art Night" events, aiming to develop the festival into a comprehensive platform for corporate brand experience and space value-added. In 2021, the Plant Dyeing Earth Art Festival debuted in Guangze, Fujian, combining plant dyeing with earth installation art to bring together creative and industrial forces. Other events include the Wudi Earth Art Festival in Jiangxi and the Gushan Earth Art Festival in Beijing. These efforts seek to integrate art with nature and regional culture, creating new opportunities for the inheritance and innovation of regional culture and the enrichment of people's spiritual lives.

These art activities differ from the earlier "Land Art" in concept, but in terms of visual form, they all share the concept of presenting artworks in natural environments. The difference is that the spatial scale of the artworks is gradually decreasing, becoming outdoor installations or sculptures within the "Land Art Festival."

Plant Dyeing Earth Art Festival

Where should Land Art go?

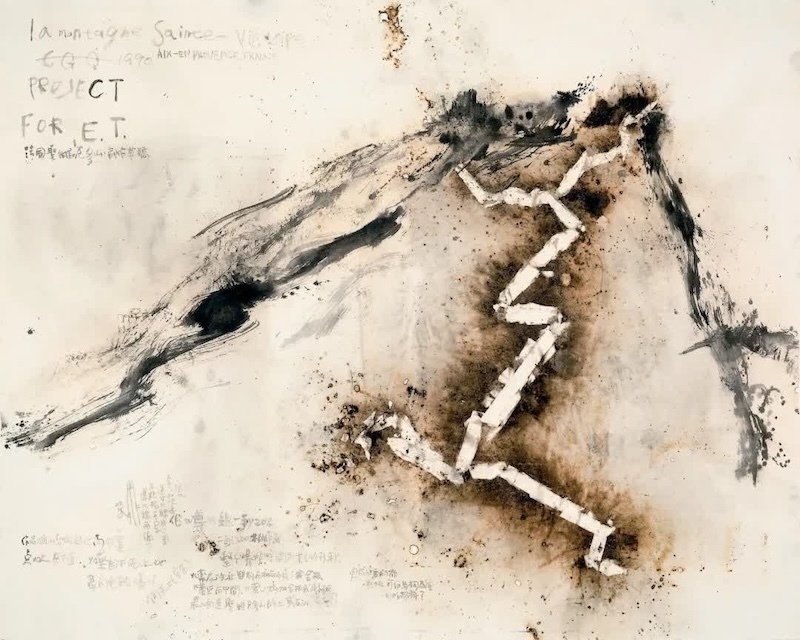

Returning to the "Rising Dragon" project, using gunpowder as a medium is a hallmark of Cai Guo-Qiang's work. His long-running project, "A Plan for Aliens," which began in 1989, includes "Rising Dragon." In 1993, Cai Guo-Qiang created "Extending the Great Wall by 10,000 Meters: Plan for Aliens No. 10." Under his guidance, volunteers, starting at the westernmost site of the Great Wall, laid 10,000 meters of fuse and 600 kilograms of gunpowder along the desert ridgeline. The ignited gunpowder formed a wall of fire that cut through the vast Gobi Desert, activating the still Great Wall. This project was acclaimed at the time.

Cai Guo-Qiang, "Extending the Great Wall by 10,000 Meters: Plan No. 10 for Aliens"

After arriving in the United States, Cai Guo-Qiang visited the Nevada atomic bomb site and secretly brought firecrackers and gunpowder he had bought in Chinatown. He then created a small mushroom cloud at the site. The work, titled "Century with Mushroom Clouds: A Plan for the Twentieth Century," he later extended this artistic performance to various iconic locations, including the cover of a book. The mushroom cloud he created symbolized the human hand, the gains and losses, and contradictions of transitioning from the use of fire to the acquisition of nuclear energy. Later, his "Big Footprint" at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the "Sky Ladder" in Quanzhou in 2015 became his most famous works in China.

The Century with Mushroom Clouds: Planning for the Twentieth Century, Nevada Nuclear Test Site, 1996, photo by Hiro Ihara © Tsai Studio

Some critics believe that, strictly speaking, Cai Guo-Qiang's previous urban fireworks displays cannot be considered Land Art. However, this project in the Himalayas, because of its direct connection to the mountains, can be said to be an extension and evolution of Land Art. An insider commented: "To implement an art project in such a region, one must not only consider ecological and environmental considerations and obtain legal approval, but also respect the local culture's reverence for mountains and truly gain the public's understanding."

Although the organizers of the project emphasized that the event procedures were in compliance, "biodegradable materials" were used, and the residues were cleaned up after the fireworks, these explanations failed to quell public doubts.

A key point in Cai Guo-Qiang's team's defense is the "transient" nature of fireworks art—unlike traditional land art, which creates lasting changes in nature, fireworks are fleeting, with only a temporary impact. However, this "transient" narrative overlooks the fact that even if fireworks are fleeting, the team's deployment, equipment transportation, and on-site operations still impact the local ecology.

Shenglong: Plan No. 2 for Aliens, 1989, gunpowder, ink, paper, 240 x 300 cm. Courtesy of Cai Studio

Fu Jun, art critic and director of the Shanghai Oil Painting and Sculpture Institute Art Museum, believes that an artist's mission is to challenge boundaries, raise questions, and explore the unknown. Often, the value of art lies in its courage to "cross boundaries." However, there is no absolute freedom in art; not violating universal ethics is the bottom line.

An art scholar at the China Academy of Art, who has devoted considerable attention to land art, told The Paper that authentic land art should adhere to the principle of low impact—minimizing intervention in nature and creating works that adapt to, rather than transform, nature. Artists should abandon the anthropocentric perspective of viewing nature as a canvas and instead view it as a collaborative partner, respecting the integrity and autonomy of ecosystems. Land art should be considered restorative at a higher level—participating in the process of ecological restoration through artistic creation.

Walter De Maria's Lightning Field (1977) features a grid of 400 stainless steel poles arranged on the New Mexico plateau, waiting for the natural discharge of lightning during a thunderstorm. Transforming uncontrollable natural phenomena into the core of art, the work fuses mathematical precision with a reverence for primal energy, emphasizing the need for immersive experience and patience, challenging the paradigm of instantaneous artistic consumption.

Some art critics believe that with the development of technology, land art can also consider adopting lower-carbon, more virtual forms of expression, translating artistic perceptions of nature through digital media and virtual reality technology.

This fireworks incident clearly illustrates the core dilemma facing the current development of land art: the complex relationship between artists' self-expression, brands' commercial interests, ecological protection, and public acceptance. Land art requires a profound upgrade in its values and ethical concepts.