On April 26, the 109th anniversary of the birth of architect IM Pei (1917–2019), “IM Pei: Life as Architecture” opened to the public at the Power Station of Art (PSA) in Shanghai. This is the first comprehensive retrospective exhibition of the architect in mainland China.

The Paper recently had a conversation with Shirley Surya, the curator of design and architecture at M+, about this exhibition. In her opinion, Pei’s designs are not just buildings, but also living spaces. “Pei’s architectural concepts are closely related to daily life. He is not the kind of architect who simply pursues abstract concepts. He is more concerned with how architecture is closely integrated with people and life. How to make architecture itself a part of life.”

Entrance to the "I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture" exhibition at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai

The exhibition has six major themes: "I.M. Pei's cross-cultural heritage", "Real estate and urban redevelopment", "Art and public architecture", "Power, politics and sponsors", "Material and structural innovation", and "Reinterpreting history through design". It not only fully demonstrates I.M. Pei's unique architectural techniques, but also compares his works with society, culture and his life trajectory, showing that architecture and life are inseparable.

Opening ceremony of "I.M. Pei: Life is like Architecture"

Shirley Surya, co-curator of the exhibition, is a historian, curator and writer. She is currently the curator of design and architecture at M+. Since 2012, she has focused on the development of design and architecture in Greater China and Southeast Asia and has collected related works for the M+ collection. Currently, Shirley is planning "Why Modern? Biography of Chinese Architecture 1949-1979", an exhibition co-organized by the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal and M+, which will open in October 2025.

For Wang Lei, Pei's architecture not only demonstrates regional span and rigorous design techniques. Throughout his practice, he always maintained a belief, that is, to collaborate across cultures, social backgrounds and regions to create an architectural style that can participate in global discussions and cooperate with local or ethnic groups. When Pei was studying in the United States, he told his father: "I don't think of myself as a stranger in a foreign country." Pei also inspires us that even in a broad and unfamiliar world, we can find a sense of belonging.

Wang Lei is the curator of design and architecture at M+ and co-curator of “I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture”.

For I.M. Pei, "life is like architecture."

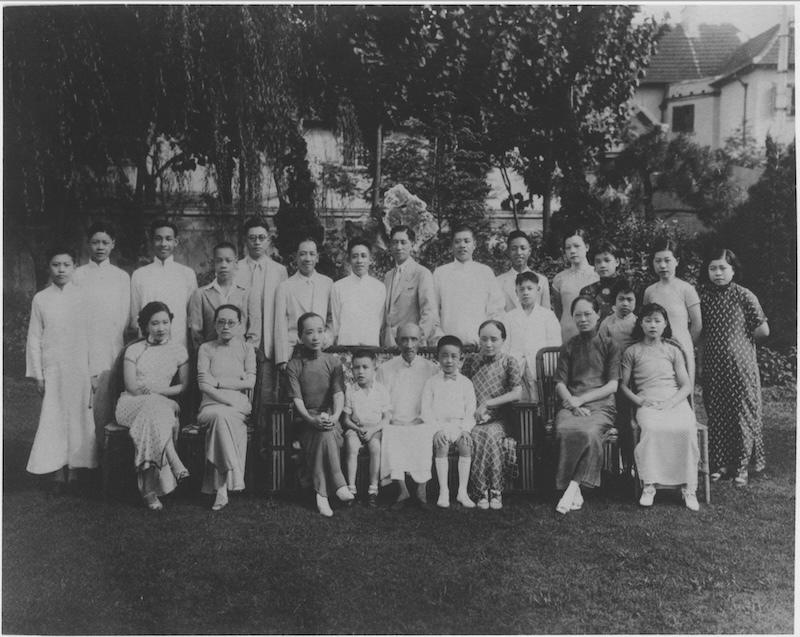

Shanghai is where he studied and grew up, and it is also the starting point of his architectural career. In 1927, 10-year-old Pei came to Shanghai from Hong Kong with his family, and studied at Shanghai YMCA Middle School and St. John's University Affiliated Middle School. This experience became an opportunity for the young Pei to get in touch with modern architecture. Shanghai in the 1930s was undergoing great changes in modernization and urbanization. The International Hotel, completed in 1934, was the tallest building in Asia for half a century. As Pei later recalled: "I was deeply attracted by its (International Hotel) height. From that moment on, I began to want to be an architect." At that time, Pei often traveled between Suzhou and Shanghai, shuttling between Jiangnan garden buildings with specific history and culture and modern landscapes of international metropolises. These early experiences of multicultural spaces inspired him to explore and interpret local and historical prototypes in a cross-cultural and modern environment.

Old photos of the International Hotel

The conversation with curator Wang Lei begins in Shanghai:

Art, history and architecture combined

The Paper: This exhibition is held in Shanghai. Going back to the starting point of his architectural career, what impact did life in Shanghai and Suzhou have on I.M. Pei?

Wang Lei: Shanghai is very important to Mr. Pei. When he was a teenager, he saw the International Hotel under construction, which inspired him to become an architect. However, I discovered in my research that his interest in the International Hotel was not only limited to the building, but also because the International Hotel was jointly invested and built by the Four Banks Savings Association of Chinese National Capital. It was not built on the Bund, but in the city center. This was a huge achievement for the Chinese at that time. Therefore, Mr. Pei's choice of a career in architecture also had a certain sentiment of saving the country through industry.

The Pei family took a group photo in the garden of Pei Zuyi's residence (owned by the Bank of China) on Fuxing Road (now Wukang Road) in Shanghai. Back row: I.M. Pei (third from left), Pei Zuyi (sixth from left), sitting: I.M. Pei's grandfather, Litai Pei (fifth from left), 1935. © Copyright, provided by Pei Qia

I was a little surprised at first that he had this awareness, until I learned about his good friend Tao Xinbo (SP Tao, born in Nanjing, Jiangsu in 1916, went to Shanghai with his family at the age of 10, and studied at the Sino-French School and Aurora University. After the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War in 1937, he left China to develop his own career and later immigrated to Singapore in the 1960s. He was the chairman of Singapore Xinguang Group and the founder of Nanjing Jinling Hotel). The two not only collaborated on construction projects, but were also very close friends. Tao Xinbo grew up in Shanghai. Although Shanghai was already an international metropolis at that time, the semi-colonial feeling made him feel uneasy.

At the exhibition, I.M. Pei talks about his experience in Shanghai.

Their generation's profound understanding of Chinese culture and national character, combined with Mr. Pei's interest in architecture, has led him to not only view modern architecture as a Western concept, but also to think about how to integrate modernism into China's construction.

As a city, Shanghai is very close to I.M. Pei’s hometown, Suzhou. The exquisiteness and uniqueness of Suzhou gardens had a profound influence on Mr. Pei. In the impact of the two cultures, he began to think about how to integrate tradition and modernity in architectural design.

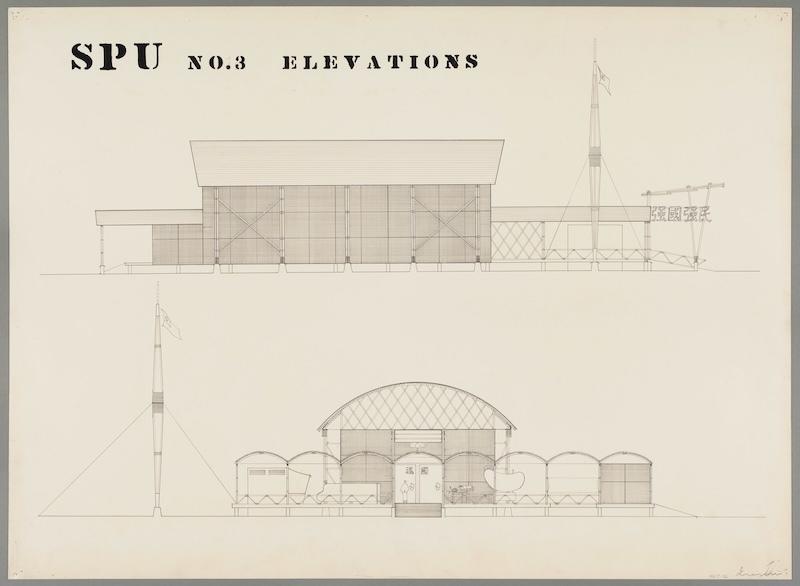

Exhibition entrance, a reconstruction of “Standardized Propaganda Stations in China, War and Peace” (1940), designed by I.M. Pei for his undergraduate thesis at MIT. Exhibition view of “I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture”, 2025, Power Station of Art, Shanghai Image courtesy of Power Station of Art, Shanghai

The Paper: Pei began studying architecture in the United States in 1935, with Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer as his mentors. As an architect in the early era of "globalization", what impact did the cross-cultural background have on Pei? What is the ongoing dialogue between "tradition" and "modernity"?

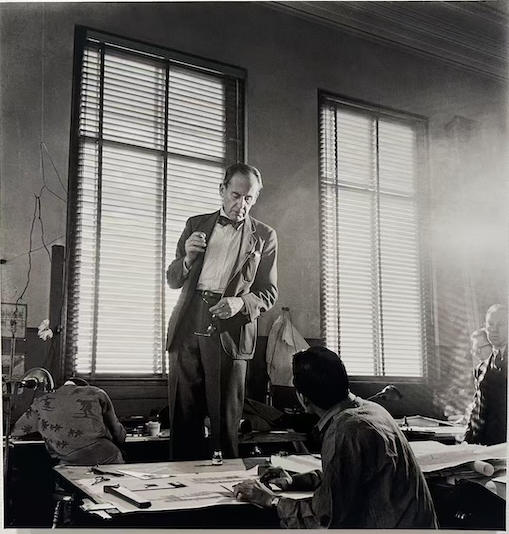

Wang Lei: As the founder of the Bauhaus School, Gropius's ideas have profoundly influenced modern art. He advocated that architecture should integrate modern technology and art, emphasizing that architecture is not only a copy of traditional forms, but also the use of the latest materials and technologies to create new architectural languages. This is also reflected in his attitude towards historical architecture. When Gropius taught at Harvard, he cancelled the course of architectural history. He did not think that architectural history was an object to be imitated, and architecture should be active and innovative. Secondly, Gropius advocated that architecture should not only serve the elite, but also benefit all social classes. Furthermore, he believed that design should not be limited to the building itself, but should return to craftsmanship. The "mechanization" he mentioned was not derogatory, and machinery and art could be integrated.

Walter Gropius at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

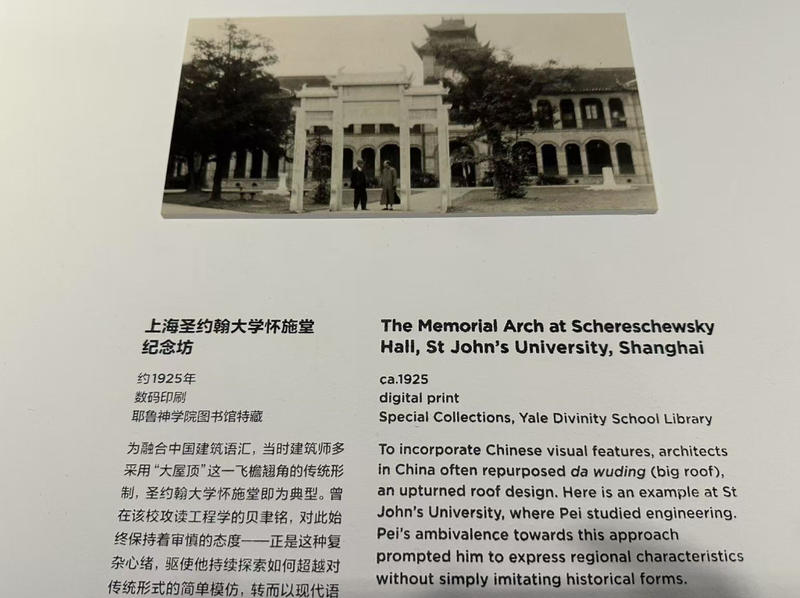

After leaving Shanghai, Pei first went to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The first generation of Chinese architects, including Fan Wenzhao, Yang Tingbao, Liang Sicheng, Tong Jun, and Chen Zhi, all graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. But the study there did not meet his expectations. Soon, he decided to transfer to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), because MIT not only focuses on the aesthetic expression of architecture, but also emphasizes concepts rather than forms. This focus on technology and innovation is very important to Pei.

At the exhibition, I.M. Pei presented his undergraduate thesis at MIT, "Standardized Propaganda Stations in China during War and Peace"

I.M. Pei, Standardized Propaganda Stations in China, War and Peace: Elevation No. 3, 1940, ink on paper. Courtesy of the MIT Museum. © MIT Museum

Later, in addition to following Gropius, another reason for going to Harvard was because of his wife, Lu Shuhua (Lu Ailing). After graduating from Wellesley College, Lu Shuhua went to Harvard University's School of Design to study landscape architecture, so I.M. Pei was able to communicate with Lu Shuhua's professor. This had a great influence on him, prompting him to decide to apply to Harvard University and enroll in December 1942 (I.M. Pei received a master's degree in architecture in 1946, but Lu Shuhua dropped out of school after her eldest son, Pei Dingzhong, was born in 1945).

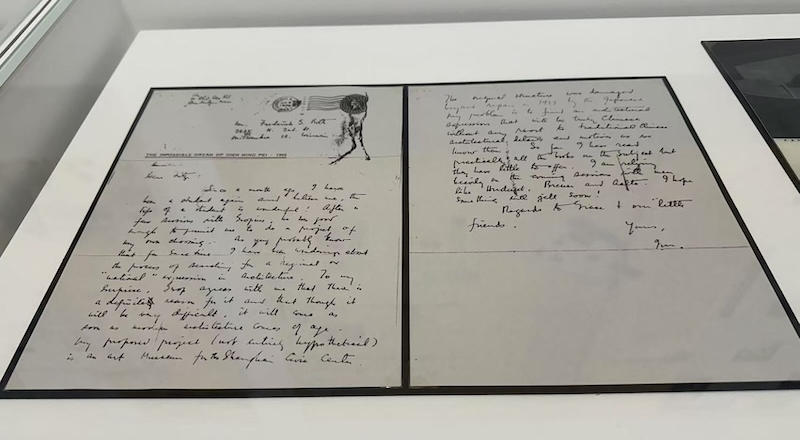

We don’t know all about Pei’s study life at Harvard, but in a letter to his classmate Frederick S. Roth, he explained the original intention of his graduation thesis design: “I have always been thinking about how to seek the expression of regional or ‘nationality’ in architecture… The difficulty lies in how to create an architectural language that is essentially Chinese without using any of the Chinese architectural decorative elements and symbol systems that we are familiar with.”

At the exhibition, I.M. Pei’s letter to his classmate Frederick Ross

This letter was written in 1946, when the concept of "regionalism" had not yet been mentioned in the architectural discourse system. "Regionalism" focused on the architecture of different regions and believed that architecture should be diversified rather than centered on Europe and the United States.

Although Pei was more influenced by Marcel Breuer during his time at the School of Design, he also regarded Walter Gropius, who later became the dean of the School of Design in 1938, as a "good teacher". Gropius developed different modeling schemes to build an efficient and humanized architectural environment under limited conditions, which attracted Pei.

In the first section of the exhibition, you can see some of Pei's works from his student days. These works are not luxury homes built for the wealthy, but designed for residents of different social classes. These designs often involve the concept of prefabrication, which means that different parts of a building are manufactured in a factory and then transported to the site for assembly. This prefabricated building can not only speed up the construction process, but also reduce costs. It is particularly suitable for large-scale, economical and practical residential construction. The use of this technology is the concrete embodiment of the "modern technology" advocated by Gropius in architecture.

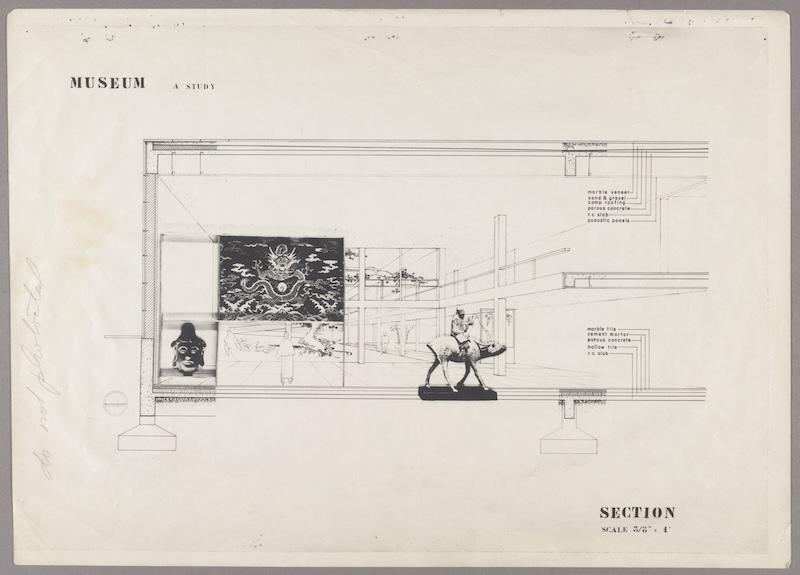

I.M. Pei, Sectional drawing of the design for the Chinese Art Museum in Shanghai for his master's thesis at Harvard Graduate School of Design, 1946. Courtesy of the Francis Loeb Library, Harvard Graduate School of Design.

The difference is that in I.M. Pei’s master’s thesis on architecture at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, which was about the design of the “Shanghai Museum of Chinese Art,” it was not the mentor who influenced the student, but the student who influenced the mentor.

Mr. Pei's design looks like a square box from the outside, but when you enter and admire the artworks in the exhibition hall, you will see the garden scenery, which shows that he attaches great importance to spatial treatment.

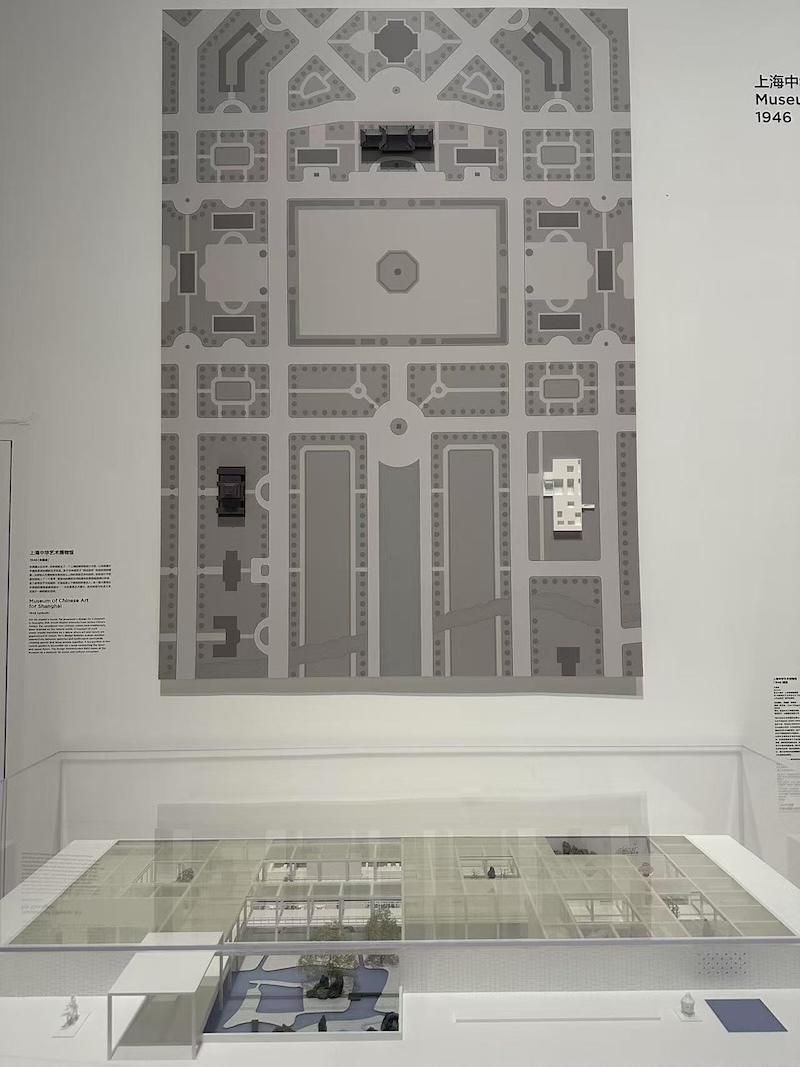

Exhibition site, floor plan and model of the “Shanghai Museum of Chinese Art” (1946), a model produced in 2024 by M+ in collaboration with the Chinese University of Hong Kong for “I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture”.

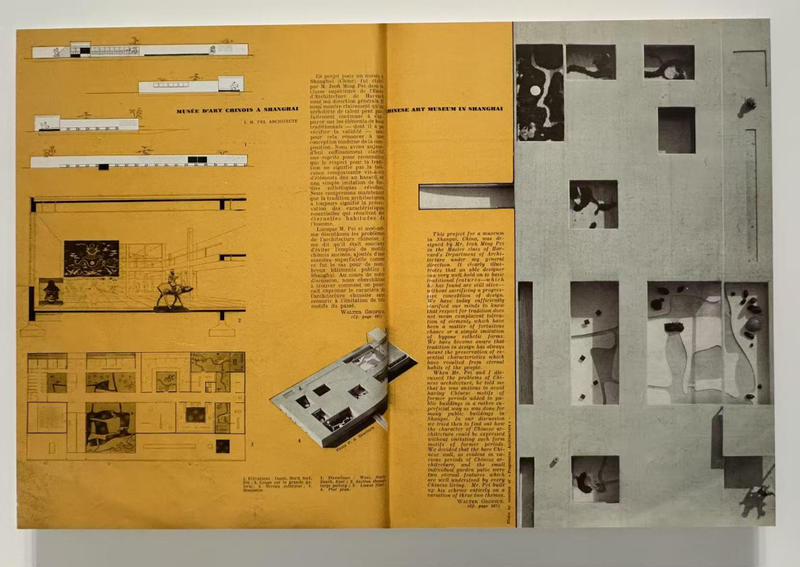

Gropius was deeply inspired by this. He did not expect that modern architecture could be so integrated into tradition. The February 1950 issue of the French magazine L'architecture d'aujourd'hui introduced how Gropius influenced the younger generation of American architects. Almost all of it was works by Gropius and his students. However, only the design plan of the "Chinese Art Museum" by I.M. Pei was presented across the page. Gropius commented on the "independent small patio garden" and "plain Chinese-style walls" designed by I.M. Pei.

Walter Gropius' article "Shanghai Chinese Art Museum", published in "Architecture Today" No. 28, February 1950

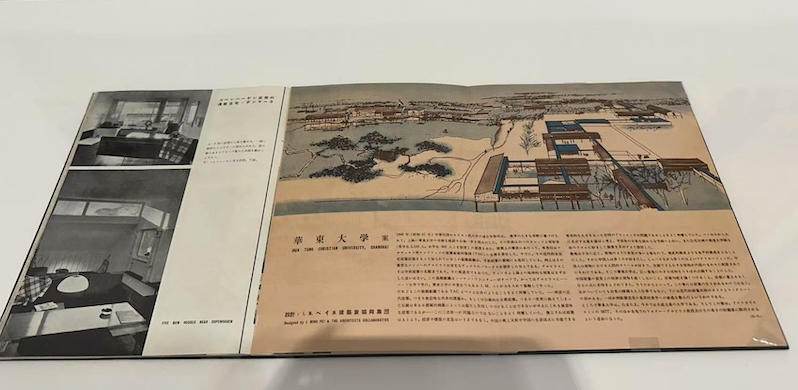

This issue of Architecture Today also features the design of East China University in Shanghai by The Architects Collaborative, a firm co-founded by Gropius in 1945 and one of which I.M. Pei worked. This was Gropius' first Asian project, commissioned in 1946 by the United Board of Christian Universities in China, the organization behind I.M. Pei's alma mater, the Shanghai St. John's University Affiliated High School. Gropius invited I.M. Pei, who was then an assistant professor at the Harvard University School of Design, to participate in this project. Just like the design plan for the "Shanghai Museum of Chinese Art" conceived by I.M. Pei for his master's thesis, the design of East China University is based on human scale and is closely related to the landscape. The plan is signed "I. Ming Pei & The Architecs Collaborative", which shows his mentor's recognition of him.

The exhibition includes documents related to East China University.

Although the campus of East China University was not built in the end, the planning map left behind shows Pei's thinking. He did not regard the building as an independent entity, but made the building and the natural environment highly integrated in the campus layout.

Top: Courtyard, I.M. Pei, 1938; Bottom: Panoramic Ink Painting of the Early Campus Plan of Tunghai University, Chen Qikuan, I.M. Pei Architects, 1954

This also foreshadows a feature of his future architectural style - his "globalization", not a formal mix and match. From the outside, many of Pei's buildings are modern, and there is no Chinese style at all. But once you walk in and start to "experience" the space, you will slowly feel the Chinese rhythm and the meaning of traditional gardens. This fusion is not a deliberate collage, but a natural combination, a kind of "cultural fusion".

The Paper: The design of the "Shanghai Chinese Art Museum" shows Pei's interest in public cultural buildings. Pei's most well-known works include many museum buildings (including the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the modernization plan of the Louvre in Paris, the Suzhou Museum, the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the Miho Museum in Japan, etc.). What do you think of his public cultural building design and the dialogue between art and architecture?

Wang Lei: The section corresponding to "Museum Design" is "Art and Civic Form". Actually, I am not very satisfied with the Chinese translation here. "Civic" is not just as simple as "public building", it emphasizes more on "publicness" - a concept of space.

Exhibition view of “I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture”, “Art and Public Architecture” section, 2025, Power Station of Art, Shanghai. Image courtesy of Power Station of Art, Shanghai

Mr. Bei grew up in a Suzhou family. For him, art is not just about famous paintings and calligraphy. He thinks Taihu rocks, bonsai, and gardens are all part of art. This broad understanding of art is deeply rooted in the cultural environment in which he grew up.

When he was studying at MIT, he had an assignment to draw a human figure, and his drawing style was obviously influenced by Cubism. In terms of architecture, it is "Geometry", which is not only a visual language, but also an emphasis on order, sense of proportion, and spatial logic.

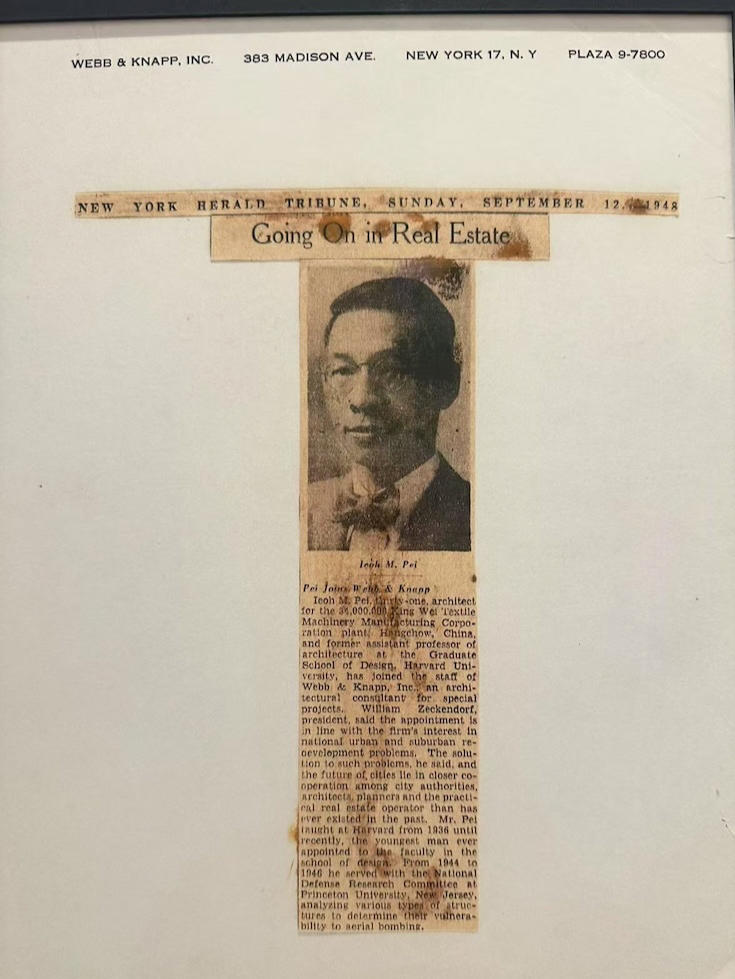

"I.M. Pei Joins Webernap," New York Herald Tribune, September 12, 1948

In fact, before designing public buildings, his contribution to American real estate and urban reconstruction in the 1950s and 1960s is little known. But when he worked for developers, he was not just doing business, he also strived to build outstanding buildings. For example, as early as ten years before the high-end office space style became popular, I.M. Pei designed a fashionable duplex penthouse office for real estate developer William Zeckendorf. This office is located on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, New York, and was one of the renovation projects of the company's headquarters. It was built between 1950 and 1951. The office is divided into control room, lounge and gallery, and the dining area on the upper floor has a landscape terrace, a sculpture by Gaston Lachaíse, and artworks borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. (Note: In 1951, MoMA launched the "art loan service". This service allows the public to rent artworks selected by the museum's curators and trustee advisory committee for two months, after which they can choose to buy or return them. This service lasted until 1982, becoming a pioneer for other international art institutions to follow suit. Of course, he was not the only architect to do this. In the 1940s and 1950s, the relationship between the architecture and art worlds was very close. At that time, people like Philip Johnson (American architect and architectural theorist) - one of Mr. Pei's classmates at Harvard - worked at MoMA, so their generation was active in the circle of intersection between art and architecture, but I.M. Pei was indeed a special one.

Exhibition view, New York Sunday News article "Tycoon Headquarters: Real estate magnate Bill Zeckendorf tries to run his business from his dream office", published on May 22, 1955

His first museum project was the Everson Museum in New York in the early 1960s. This project was not just about “building an art museum”, but was about urban regeneration and the revitalization of the city center. In other words, he combined architecture with social issues such as “public space” and “citizen life” from the beginning.

The Everson Museum of Art in New York under construction in 1967.

Since that project, Mr. Pei has received many important museum commissions, such as the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and the most famous renovation project of the Louvre in Paris. The two museums have always had close cooperation and trust each other and I.M. Pei. The Louvre project was commissioned directly without even bidding, which is rare in the architectural world. The reason why Mr. Pei can do this is not only because he is a good architect, but also because he needs to handle various relationships well.

In the exhibition, there is a narrative about the materials in the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

The Paper: The several museums just mentioned are all regarded as I.M. Pei’s masterpieces. What are the similarities and differences between them?

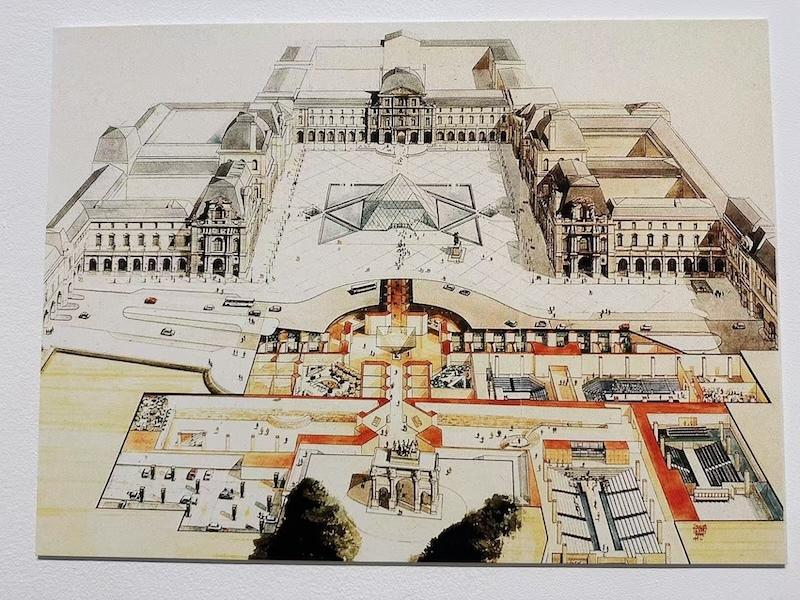

Wang Lei: Pei thinks differently about each museum project. He is not the kind of architect who “formulates”. The strategy for each project is unique and specific. For example, the Louvre is a special project—it is not a new building built from scratch, but a palace with hundreds of years of history, a national cultural symbol of France.

A bride poses in the Passage Richelieu at the Louvre Project (1983–1993), Paris, 2021. Photo: Giovanna Silva. Commissioned by M+, 2021. © Giovanna Silva

The problem with the Louvre is that its entrance was originally very divided, and people couldn't figure out which side to enter. So I.M. Pei came up with a very clear idea: the entrance must be in the center and underground. This way, once visitors enter, they can clearly choose which side of the exhibition hall to go to. It's very clear. He thought very carefully about the flow of space, not just for beauty, but from the perspective of publicity - he thought about how to allow the public after the 1980s to better enter and flow through the museum building that was built centuries ago.

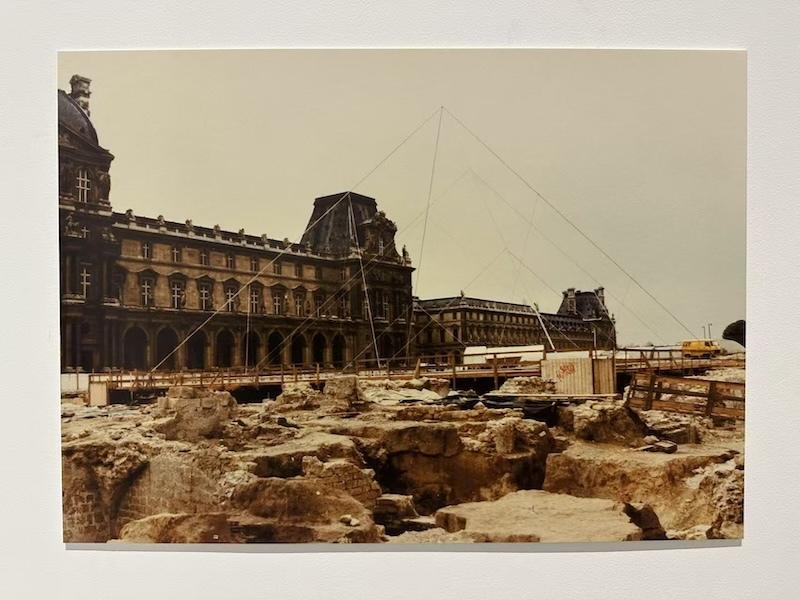

The Grand Louvre project, a glass pyramid under construction

He even considered where the tourist buses would park and how the museum would be self-sustaining in the future, so he added shopping centers and other commercial spaces underground. His design also reconstructed the relationship between the Louvre and the city, such as the connection with the other side of the Seine. It can be said that Pei regarded the Louvre as an "urban project". The design of this kind of museum is no longer just a question of the building itself, but a deep design of how to shape public space and influence the urban structure.

Louvre Carrousel shopping center corridor.

But the Miho Museum in Japan is completely different. He first asked the client: Why do you want to build this museum? What is the significance of this museum? The client is a religious institution, whose core belief is that "beauty is sacred" and hopes that the museum will be like a "temple".

So Pei decided that tourists could not just get off the bus and enter. The entire path had to be "winding and secluded" - just like Tao Yuanming's "Peach Blossom Spring", slowly leading people in. He did not design it this way because he liked the Chinese style, but because he understood the spirituality of this museum and needed to create a sense of ritual of "entering a temple".

View of the suspension bridge extending to the Miho Museum (1991–1997), Shigaraki, Shiga Prefecture, 2021. Photo: Tomoko Yoneda. Commissioned by M+, 2021. © Tomoko Yoneda

When it comes to the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, the thinking logic is completely different. The question at the beginning of this project was: "What do we want to collect?" The answer is - to collect Islamic art spanning many centuries and many regions, from Turkey, Arabia, Persia to Central Asia, a very wide span. So I.M. Pei began to study the holy places and architectural traditions of these regions. He finally chose an early mosque in Cairo, Egypt as a source of inspiration - this building is very geometric, not a typical Turkish style, nor an Arabic style, but with a more universal and more integrated visual language. He thinks this is very suitable for Qatar - because Qatar itself is a young country, without an established architectural form, it needs an open, inclusive and diverse design.

Exhibition site, model of the Museum of Islamic Art

Therefore, the Louvre, Miho Museum and Doha Museum of Islamic Art are completely different. This “one case, one strategy” is exactly what makes him the most unique and profound architect.

Understand the relationship between architecture, city, society and people

The Paper: How do you define the exhibition title "Life is Like Architecture"? What is the most impressive discovery you made during the seven years of research and exhibition preparation?

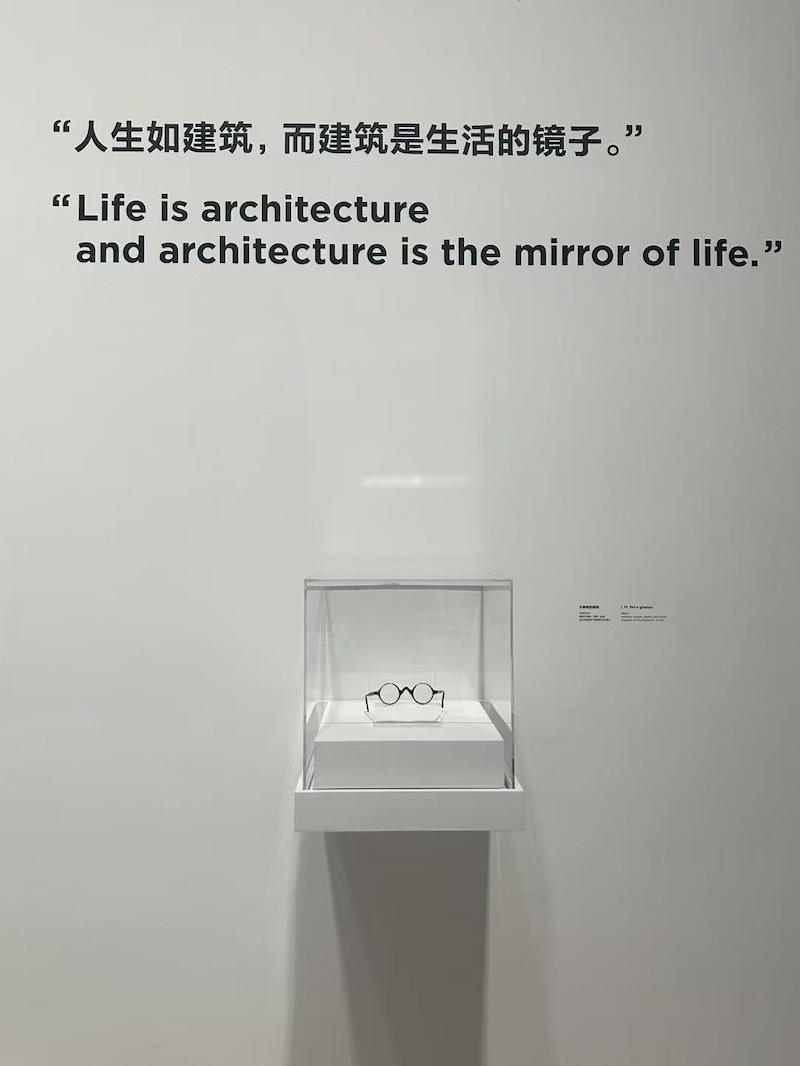

Wang Lei: When we decided to name this exhibition "Life is Architecture", it actually started from a saying by I.M. Pei - Life is architecture and architecture is the mirror of life.

Exhibition site

This sentence seemed a bit strange to me at first, after all, we rarely directly associate architecture with life. It was not until I read more about Mr. Pei's life and thoughts that I really understood his unique insights on this relationship. When he was traveling and communicating with Marcel Breuer, he mentioned that he saw how people in the city lived and how they moved around in the city, and this way of life was like a part of architecture.

I.M. Pei's architectural philosophy is closely related to daily life. He is not the kind of architect who simply pursues abstract concepts. He is more concerned with how architecture can be closely integrated with people and life. How to make architecture itself a part of life. This is also one of the reasons why I chose this name, because it can well convey Mr. Pei's thoughts - architecture is not only to show artistry, but also to serve human daily life.

Exhibition site

During the curatorial process, I gradually realized that Pei's design was carried out in a very pragmatic and systematic way. He did not simply shape the building through appearance, but responded to the needs of life through every detail and every design decision. For example, the glass pyramid of the Louvre was still turbid green at the time. Mr. Pei asked the French glass factory to design a glass with extremely high transparency for this purpose, which promoted the technological progress of the entire industry.

An account of how the Louvre's glass pyramid was built is included in the exhibition.

Another example is the roof of the church of the Miho Museum, which is made of stainless steel. The zigzag roof is not only visually striking, but also reflects Mr. Pei's unique understanding of architectural structure and materials. His architecture is always exploring the boundaries between technology and art, and he can always combine the two seamlessly through innovation. The same is true for the Bank of China Building in Hong Kong. Its budget is only one-third of that of the HSBC Building. This difference means that I.M. Pei made many innovative and cost-saving design choices in the design.

Therefore, every project is a breakthrough for him, and every project is a new challenge and creative opportunity.

Model of the Miho Museum church roof

For me, what makes Pei special is how he deeply respects different cultures while maintaining in-depth thinking about his own culture. In the first section of the exhibition, there is a letter written to his father, Bei Zuyi, on May 13, 1939, in which he wrote, "I don't think I shall feel strange in a strange land." Later, I learned that "a stranger in a strange land" came from Wang Wei's "alone in a strange land" in the Tang Dynasty, which gave me a deeper understanding of Pei's interweaving and collision between cultures. This letter was written just two years after he arrived in the United States, but he was able to express his respect for his own identity and other cultures through this cultural self-awareness. Although this idea is not directly related to the architecture itself, it has profoundly influenced his way of dealing with cultural differences in architecture and has also inspired the present.

Letter from I.M. Pei to his father, Tsu-Yi Pei

The Paper: In the exhibition, we see I.M. Pei’s close collaboration with artists such as Henry Moore and Zao Wou-Ki. I.M. Pei and his wife also collect art. How did modern art, Cubism, and his interactions with artists inspire I.M. Pei? What does integrating art works into architectural space bring to architecture?

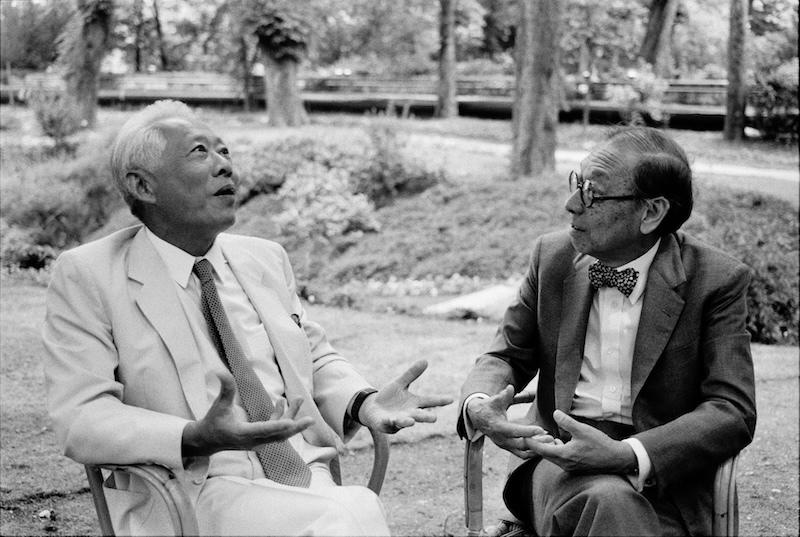

Wang Lei: Pei’s collaboration with many artists is not just a superficial or honorary “co-signature”. He and the artists he collaborated with were often very good friends in person and were very interested in each other’s work. Their collaboration was based on a common sensitivity to space, form, and emotion.

I.M. Pei and Zao Wou-Ki in the Tuileries Garden, Paris, circa 1990. Photo: Marc Riboud. © Marc Riboud/Fonds Marc Riboud au MNAAG/Magnum Photos

Mr. Pei and Zao Wou-Ki are typical examples. In the early 1970s, Zao Wou-Ki experienced the loss of his wife and stopped using ink and wash for a while, only painting small works. It was I.M. Pei who encouraged him, saying: Why don’t you try to paint larger ink paintings and create a group of works for the Xiangshan Hotel I designed in Beijing? Facts have also proved that Zao Wou-Ki’s ink and wash have an inherent resonance with space.

This is not a simple question of "I need a few paintings to decorate my building", but a collaboration that starts from the concept. Art and architecture are mutually contextual and complement each other.

Zao Wou-Ki’s ink paintings installed in a room next to the Four Seasons Court lobby at the Fragrant Hill Hotel (1979–1982), Beijing, 2021. Photo: Tian Fangfang. Commissioned by M+, 2021. © Tian Fangfang

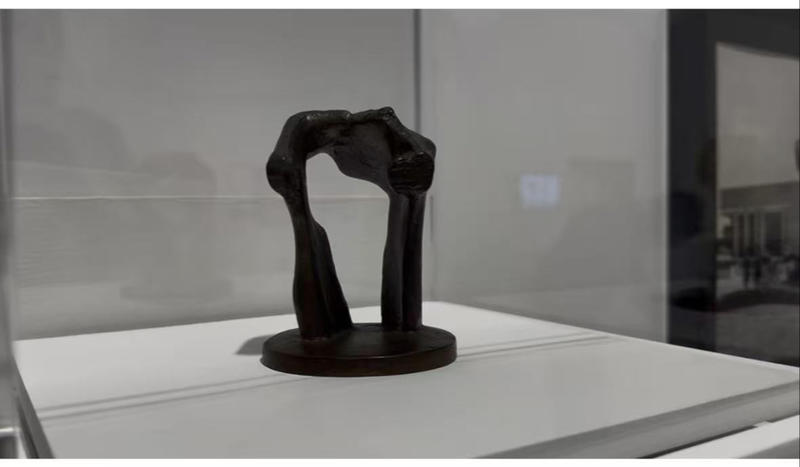

His collaboration with British sculptor Henry Moore was another level of relationship - more spatial. They collaborated many times, the first time being at the Clear Lake Rogers County Library in Columbus, Indiana, where he designed a plaza for public gatherings and invited Henry Moore to create a work as a symbol of the plaza. Moore suggested remaking his small work Large Torso: Arcb (1963) into a giant bronze sculpture Large Arcb (1971). After the project was completed in 1971, Moore became a close partner and friend of I.M. Pei.

Exhibition view, Henry Moore's sculpture for the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library

They had a more important collaboration in the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The plan layout of the gallery itself is an abstract "knife edge shape", and the sculpture Moore placed at the entrance of the gallery is called "Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece", which is sometimes translated into Chinese as "Knife Edge". This work and the building are intertextual in formal language, and you will feel that they are in dialogue, and the sculpture and the building together constitute a complete spatial narrative.

Their third collaboration was at the OCBC Bank headquarters in Singapore, where Mr. Pei specifically asked Moore to create a public sculpture to be placed in front of the bank building. It was one of the earliest public sculptures in Singapore, setting a new urban rhythm for this Asian city.

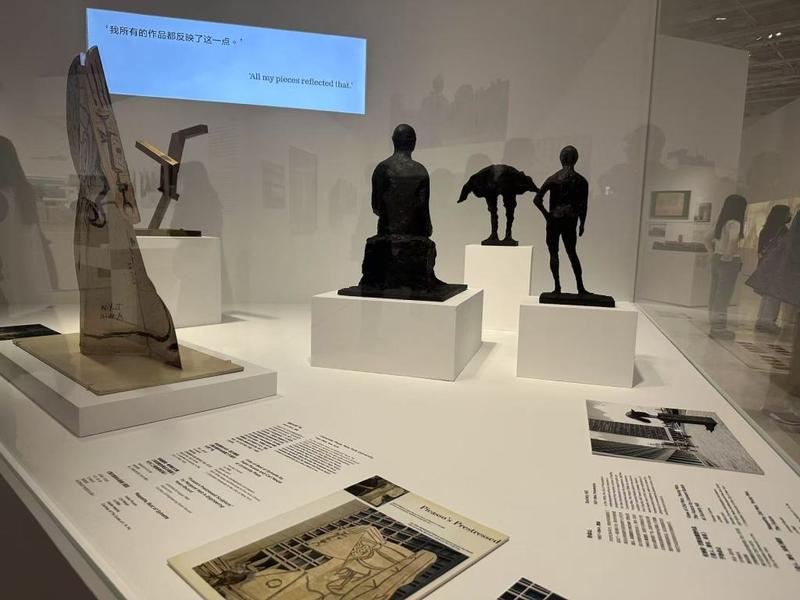

In the exhibition, I.M. Pei’s architecture and artists’ works are sorted out.

I would also like to talk about why Mr. Pei invited artists such as Cai Guoqiang and Xu Bing to participate in the opening exhibition of Suzhou Museum, which he curated. His interest in these artists is not accidental. They have collaborated many times. As Chinese people, they are both interested in Chinese history and tradition. He always believes that tradition cannot be consumed superficially. It needs to be deeply understood and transformed before it can be re-expressed in a modern language. Their creations are not copied from tradition, but through continuous research and reinterpretation, they translate the ancient elements of Chinese culture into a contemporary visual language. This is a kind of "re-creation" (reinterpretation), not copying (copy) or nostalgia (nostalgia).

Exhibition site, Cai Guoqiang's works and Suzhou Museum's opening exhibition documents

The role of art in architecture is never just "embellishment" and decoration. Mr. Pei's understanding goes far beyond this level.

Of course, we must also admit that artworks do not necessarily directly affect the structure or form of buildings, but even so, their existence is still crucial. Especially for I.M. Pei, he always regards architecture as a "cultural project".

The Paper: The exhibition uses a large number of models, drawings, images, and documents. How do you deal with these materials that are "highly professional" but may make the public feel distant?

Wang Lei: Compared with professional documents, we have a lot of documentaries. I noticed that the audience was completely attracted by those films during the M+ exhibition in Hong Kong. Because these images not only show I.M. Pei's architectural works, but also show how he personally explained and interpreted these works. In fact, it was not until June 2023 that these precious documentaries were found and presented after overcoming various copyright difficulties.

These documentaries allow the audience to see how Pei himself thinks and how he explains his design concepts. For the public, the strongest feeling is that through these images, they can see how Pei himself expresses his understanding of architecture. This is a very powerful way of presentation, especially in architectural exhibitions, where images allow the audience to have a more direct dialogue with the architect's thoughts.

The exhibition site, one of the many documentaries about I.M. Pei

For example, a documentary recorded the experience of I.M. Pei when he just won the National Gallery of Art in Washington. At that time, although he had already achieved considerable fame, his work had not yet been built. In the documentary, I.M. Pei was observing the interaction between the crowd and the building in the Rockefeller Center Plaza in New York. He walked and explained at the same time. This way of observing public space is very interesting.

Another documentary tells the story of Pei's relationship with the client and how he handles communication and collaboration in architectural projects. The third documentary delves into his construction methods when using building materials such as concrete, which is closely related to his architectural designs. These documentaries not only show his architectural philosophy, but also how he innovates architectural forms through his understanding and application of materials. All of these documentaries were filmed in 1970 and produced by Boston's public television station, which is extremely valuable.

“I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture” exhibition, 2025, Power Station of Art, Shanghai. Image courtesy of Power Station of Art, Shanghai

Of course, in addition to these documentaries, models and drawings are still very important parts. These physical objects are archives left by I.M. Pei's early studio. Although many original materials no longer exist, we can only use replicas to present some concepts and ideas of the design process. Although replicas cannot completely restore the original appearance, they are necessary tools for us to show the architect's thoughts and design process. The challenge of architectural exhibitions is not only to present the architect's creative process, but also to allow people who do not understand architecture to understand the relationship between architecture and the city and society.